Origins of the Battle Staff NCO Course

Guest post from SGM (Ret.) Bill Smolak, Team Lead, BSNCOC Developer

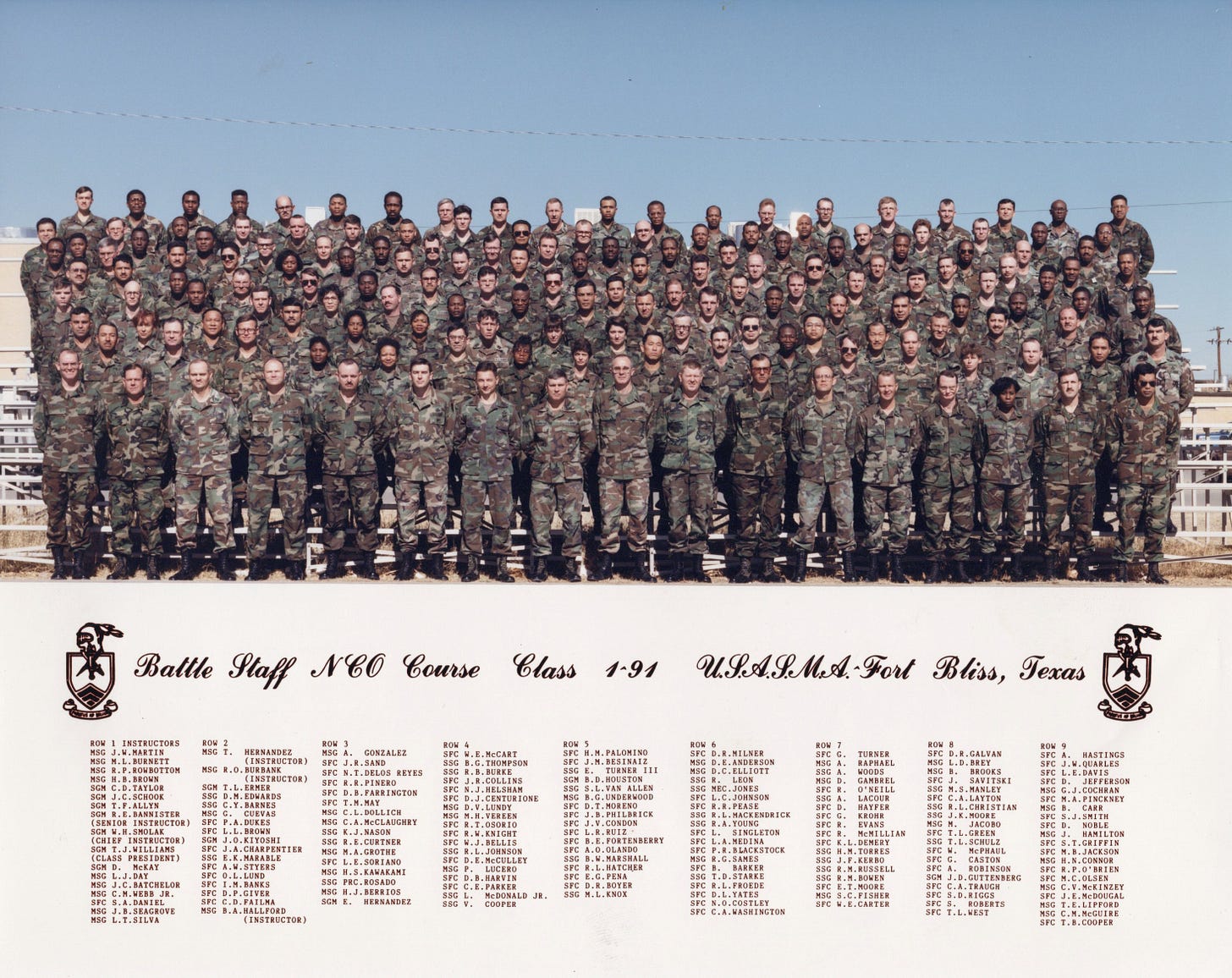

Sergeants Major Academy Battle Staff NCO Course developers, instructors and graduates, Class 1-91.

[Ed. Note: This is a summary from a fuller monograph provided by NCO Leadership Center of Excellence Hall of Honor awardee SGM (Ret.) William Smolak, which is available in full at the bottom of this article.]

I completed the Sergeants Major Course (SMC) in 1987, Class 29. I was selected to stay at USASMA [Ed. note: now NCOLCoE] to help develop the Personnel and Logistics Course (P&L). It was a small team led by SGM Charles Steward. In addition to myself, team members included SGM Seth Fuller, SGM Thomas Gulick, SGM Robert Judd, and SGM Terry Trent. The new course would parallel the instruction of the [existing] Operations and Intelligence Course (O&I); however, the two courses would be separate entities. O&I began instruction in about 1986.

In 1989, General Carl Vuono, the Chief of Staff of the Army, ordered USASMA to replace O&I and P&L. I was selected to lead the team in developing and fielding the new course. The direction was not to merge or combine the two courses but to replace them with a new course, the Battle Staff NCO Course. The development included fielding a team of subject matter experts, procuring facilities and equipment, creating a five-year training plan, selecting a target audience, determining course content and length, developing new lessons, and providing an additional skill identifier (ASI) (2S) for soldiers who completed the course.

I took much of my direction from General Vuono and Sergeant Major of the Army Julius Gates. Both leaders were actively involved in developing the course to ensure that it provided NCOs with training relevant to their Tactical Operations Center (TOC) duties. This was a train-as-you-fight strategy to help soldiers understand doctrine and warfighting, and how it applied to the duties in the TOC and in garrison. During the two-year project, General Vuono charged Colonel Kenneth Simpson and Colonel Fredrick Van Horn, commandants of USASMA, with meeting his intent and delivering the Battle Staff NCO Course. Both commandants, during the development and delivery phases, provided guidance and resources to ensure that we successfully developed a course from which soldiers could benefit.

The development team comprised about 35 NCOs, including lesson writers, Command Post Exercise (CPX) developers, instructors, and support personnel. The cadre ranged from Sergeant First Class to Sergeant Major. Some of the cadre were assigned to operate and train selected students on the Battalion/Brigade Battle Simulator and the Maneuver Control System (MCS). This was the first NCO training course to include a battle simulator. In the late 1980s, battalion/brigade battle simulators were procured for significant facilities. One simulator was earmarked for Fort Bliss, Texas. The simulator required an air-conditioned building. Fort Bliss did not have an air-conditioned building that could house the simulator. The BSNCOC had an air-conditioned building. Therefore, the simulator was diverted to the BSNCOC, with the caveat that Fort Bliss units could also use the device.

Course content focused on NCO duties and responsibilities in a TOC. The course learning objectives were to develop Staff Sergeants through Sergeants Major as battle staff NCOs at battalion and higher-level assignments. The course would last six weeks, culminating in a three-day CPX. The course could train up to 160 students per class. Subjects include individual duties, map reading, graphics and overlays, decision-making, preparing, reading, and implementing operational orders. This presented quite a challenge since many NCOs had never seen an operations order, read a map, or prepared overlays. It was difficult and further complicated because in 1991, there was a lack of digital training equipment. Most everything was analog. Training was done with paper, overhead projectors, and whiteboards.

The intent was to prepare NCOs for TOC operations where each NCO knew or was familiar with the duties of the other NCOs in and associated with the TOC. Today, the objective is relatively the same: “…provides training that is relevant to missions, duties, and responsibilities assigned to staff NCOs working in battalion and higher positions, both on the battlefield and in garrison environments." (2024-bsncoc-trifold.pdf (army.mil)). The training also prepared NCOs to help officers in their operations and, in an emergency, temporarily carry out their duties. Well-trained Battle Staff NCOs could be valuable assets in a TOC and garrison. Imagine an NCO who was familiar with the tasks of the other NCOs in a TOC. An NCO who could help prepare briefings, read a map, and carry out assignments with little or no supervision, a Battle Staff NCO.

A battle-staff NCO

The course was set up to simulate a brigade environment. The students were assigned to battalion or brigade classrooms that represented a cross-section of their home duty assignments. There was an infantry classroom, an armor classroom, and more. The students included supply, personnel, operations, and intelligence NCOs with various military occupational specialties, all possessing experience and assignments in, for example, an infantry battalion or higher. Supply sergeants would be assigned to the infantry classroom if most of their assignments were with an infantry unit. Each classroom could include up to 16 students, allowing for up to four S1, S2, S3, and S4 NCOs. While the priority was to train battalion-level NCOs, the class also included NCOs from higher levels of command. If a brigade-level NCO was typically assigned to an infantry unit, that NCO could be included in the infantry classroom. Other classrooms would be set up similarly for specific combat arms, combat support, or combat service support units. A typical class might be designed with a tank-heavy classroom, a mechanized infantry room, an air defense room, or a field artillery room. The class aimed to mirror the battalion-level force structure.

The three-day CPX was carried out in a separate building designed to exercise and test students on what they had learned during the course. The CPX facility was originally part of the O&I Course and, before that, the USASMA Learning Resource Center. The wooden building contained track mock-ups with radios and camouflage netting. It was noisy, and it lacked air conditioning and heat. It was a loud and uncomfortable environment.

The battle simulator provided mock operations. The MCS provided loss information related to the battle simulator operations. The course was not designed to teach tactics, so during the CPX, student operators could make operational mistakes. Because of this, the student operators were not graded on their use of the simulator. The idea was to create a battlefield environment, determine what happened and what was needed, and then respond to the event. The maneuver control system provided detailed information about personnel and equipment losses. In turn, the students would react to this information and provide a response. For example, if a unit needed MEDEVAC, the students would try to provide that support.

The CPX took the students out of their classroom environment. The CPX included daily briefings and ended with exit briefings, an overview by the class senior NCO, supported by specifics from the operations, intelligence, logistics, and personnel NCOs. While most of the NCOs might not have yet participated in these briefings, the CPX helped expose them to what might be presented by their officers. It also provided the NCOs with knowledge that could help them support the officers in preparing the briefings. SGM Phil Cantrell developed the CPX. As far back as I can remember, he was part of the growth of the O&I Course and the BSNCOC. He created a superb product.

In addition to the cadre operators of the battle simulator and MCS, each classroom provided several NCOs to be trained to operate the simulator. The cadre was the opposing force, and the students were the friendly force. During the CPX, the student operators were exchanged with other operators in the TOC. This caused a temporary breakdown in TOC operations, which could be expected in real-time. Instructors would also remove some TOC operators or interfere with operations to determine how well students could adjust to the loss of fellow NCOs. Communications would be interrupted, and it was necessary to use runners to contact nearby units.

First Battle Staff NCO Course

The Battle Staff NCO Course’s initial offering was Class 1-91, which began instruction in January 1991. It consisted of nearly 20 instructors and about 150 students. The Class comprised Staff Sergeants, Sergeants First Class, Master Sergeants, and Sergeants Major. After Class 1-91, the team improved some of the lessons. Class 2-91 consisted of about 150 students, from Staff Sergeants to Sergeants Majors. In later years, the Sergeant Major was not included in the Battle Staff target population, as similar training would be included in the Sergeant Major Course.

The course was six weeks long, with six or perhaps seven classes per year. This provided the means to train the target population over a five-year period. The target population was limited to NCOs who were or would be assigned to operational roles in combat, combat support, and combat service units. This meant that not every NCO in the Army was eligible for training in the Battle Staff NCO Course. Graduating students would be awarded ASI 2S.

As the team lead, one of the challenges was to show the Army that a team of NCOs led by an NCO could respond to direction and develop the Battle Staff NCO Course. General Vuono was precise in his direction. He visited the Academy various times to be briefed about the course by me and to guide us on his intent. SMA Gates also provided guidance and interpretation of General Vuono's direction. I went on over a dozen trips, which included Washington, DC, Fort Leavenworth, Fort Monroe, Fort Bliss, and Germany. I participated in a two-week grading of a battalion/brigade CPX in Germany. I briefed various commands, including TRADOC, and at each location.

Battle Staff has evolved over the years to support changes in Army Doctrine. It is now a four-week course of instruction that soldiers from the three Army components, sister services, and international partner nations attend. The culminating event for the BSNCOC is a Combined Arms Rehearsal (CAR). The mission and subject matter remain relatively the same but are constantly updated to track changes within the force. Today, it is a different environment that requires different methods of instruction. I am proud to say that I was a small part of developing this course. I am proud of the team, their accomplishments, today's cadre, and the support they receive from the NCOLCoE. The BSNCOC continues to be a practical, functional course.

Download the full history here [ncohistory.com link]

SGM Smolak was born in 1948 and entered the Army in July 1966. He retired in August 1991. He is from Auburn, New York. He married his wife Catsy in June 1968 and they reside in El Paso, Texas. Their daughter Natasha, her husband Jimmy, and grandson Noah live in Horizon City, Texas.